Tangled magnetic fields power cosmic particle accelerators

SLAC scientists find a new way to explain how a black hole’s plasma jets boost particles to the highest energies observed in the universe. The results could also prove useful for fusion and accelerator research on Earth.

By Manuel Gnida

Magnetic field lines tangled like spaghetti in a bowl might be behind the most powerful particle accelerators in the universe. That’s the result of a new computational study by researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, which simulated particle emissions from distant active galaxies.

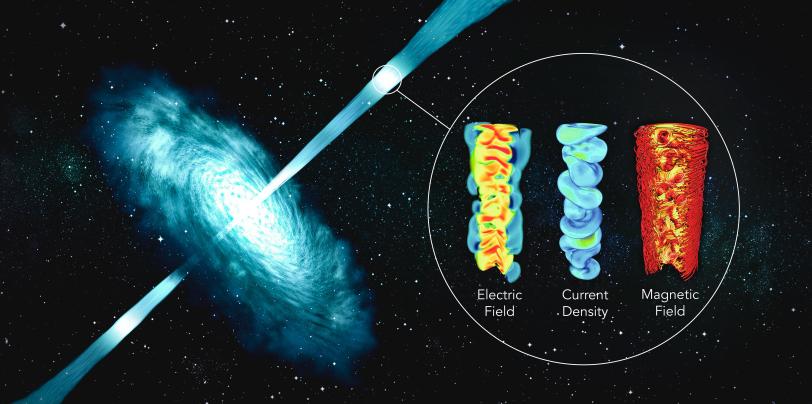

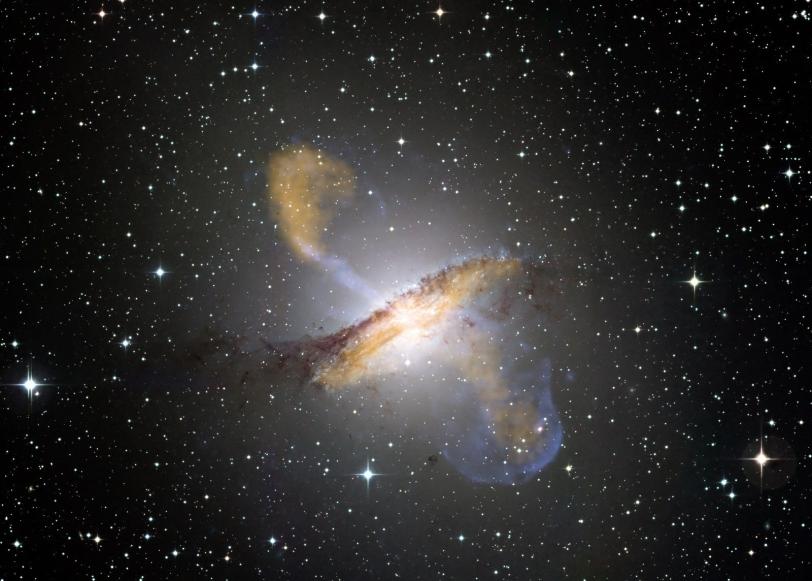

At the core of these active galaxies, supermassive black holes launch high-speed jets of plasma – a hot, ionized gas – that shoot millions of light years into space. This process may be the source of cosmic rays with energies tens of millions of times higher than the energy unleashed in the most powerful manmade particle accelerator.

“The mechanism that creates these extreme particle energies isn’t known yet,” said SLAC staff scientist Frederico Fiúza, the principal investigator of a new study published in Physical Review Letters. “But based on our simulations, we’re able to propose a new mechanism that can potentially explain how these cosmic particle accelerators work.”

The results could also have implications for plasma and nuclear fusion research and the development of novel high-energy particle accelerators.

Cosmic Jet Simulations

Simulating cosmic jets

Researchers have long been fascinated by the violent processes that boost the energy of cosmic particles. For example, they’ve gathered evidence that shock waves from powerful star explosions could bring particles up to speed and send them across the universe.

Scientists have also suggested that the main driving force for cosmic plasma jets could be magnetic energy released when magnetic field lines in plasmas break and reconnect in a different way – a process known as “magnetic reconnection.”

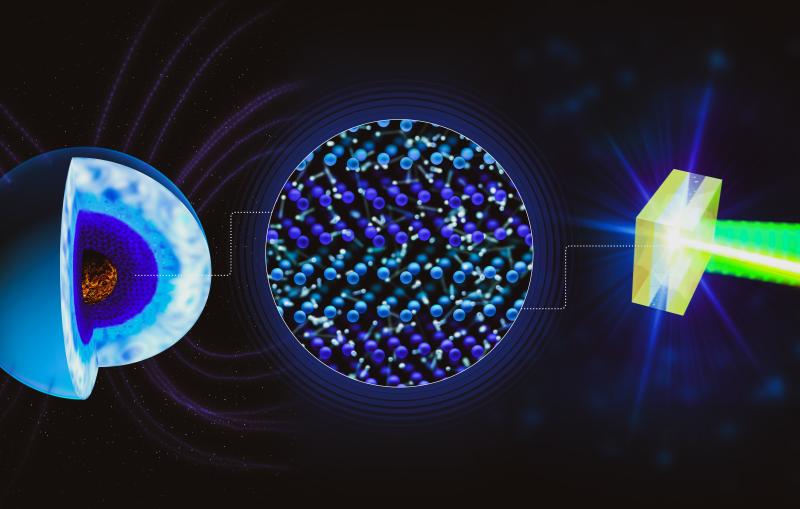

However, the new study suggests a different mechanism that’s tied to the disruption of the helical magnetic field generated by the supermassive black hole spinning at the center of active galaxies.

“We knew that these fields can become unstable,” said lead author Paulo Alves, a research associate working with Fiúza. “But what exactly happens when the magnetic fields become distorted, and could this process explain how particles gain tremendous energy in these jets? That’s what we wanted to find out in our study.”

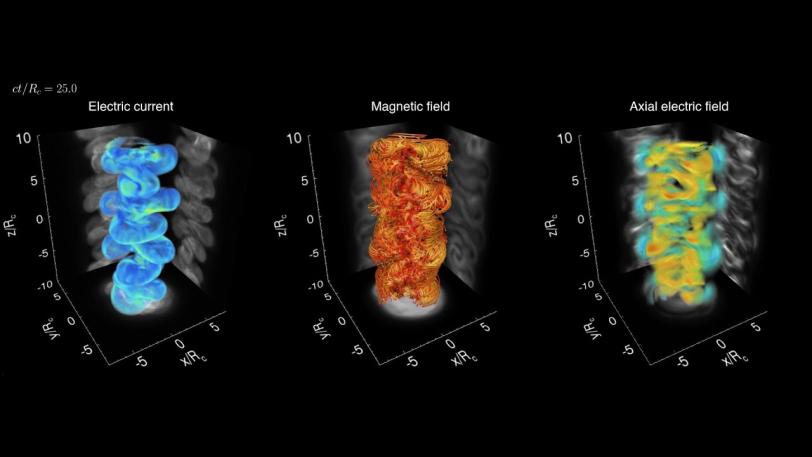

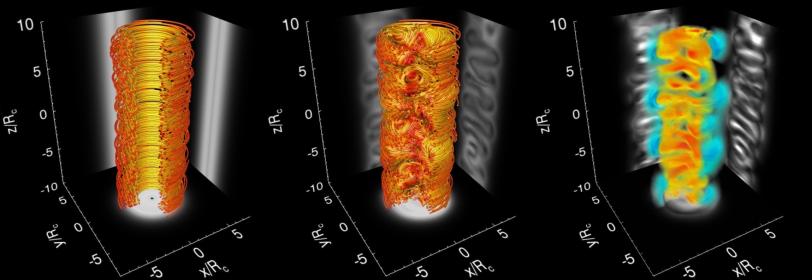

To do so, the researchers simulated the motions of up to 550 billion particles – a miniature version of a cosmic jet – on the Mira supercomputer at the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility (ALCF) at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory. Then, they scaled up their results to cosmic dimensions and compared them to astrophysical observations.

From tangled field lines to high-energy particles

The simulations showed that when the helical magnetic field is strongly distorted, the magnetic field lines become highly tangled and a large electric field is produced inside the jet. This arrangement of electric and magnetic fields can, indeed, efficiently accelerate electrons and protons to extreme energies. While high-energy electrons radiate their energy away in the form of X-rays and gamma rays, protons can escape the jet into space and reach the Earth’s atmosphere as cosmic radiation.

“We see that a large portion of the magnetic energy released in the process goes into high-energy particles, and the acceleration mechanism can explain both the high-energy radiation coming from active galaxies and the highest cosmic-ray energies observed,” Alves said.

Roger Blandford, an expert in black hole physics and former director of the SLAC/Stanford University Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC), who was not involved in the study, said, “This careful analysis identifies many surprising details of what happens under conditions thought to be present in distant jets, and may help explain some remarkable astrophysical observations.”

Next, the researchers want to connect their work even more firmly with actual observations, for example by studying what makes the radiation from cosmic jets vary rapidly over time. They also intend to do lab research to determine if the same mechanism proposed in this study could also cause disruptions and particle acceleration in fusion plasmas.

This work was also co-authored by Jonathan Zrake, a former Kavli Fellow at KIPAC, who is now at Columbia University. The project was supported by the DOE Office of Science through its Early Career Research Program and an ALCC award for simulations on the Mira high-performance computer. ALCF is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.